Dozens of Florida's workers die every year from the heat. Does anyone care?

Yesterday, November 7, 2023, Miami-Dade County Commissioners considered a heat ordinance that would be the first county-level ordinance in the nation to protect workers from excessive heat. Though the thermometer rarely, if ever, tops 100 degrees in Miami, over 100 days in Miami-Dade County every year have a heat index (the "feels like” temperature that takes into account humidity) over 95 degrees. There are no Federal laws protecting workers from excessive heat--the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, better known as OSHA, only offers voluntary guidelines for extreme heat conditions. Just three states, California, Washington, and Oregon, have state-level ordinances that require employers to give workers breaks during excessive heat. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted 41 heat-related deaths in Florida in 2020 alone. The CDC estimated that 4,200 Floridians visited the emergency room for heat related illnesses in 2021.

On Monday, the Washington Post’s Nicolás Rivero published an outstanding story on heat-related illness for workers in the United States and an overview of the Miami-Dade County Heat Ordinance. I recommend you read it.

The overview of the ordinance is simple: on very hot days workers are entitled to a 10-minute break every 2 hours, water provided by the employer and shade. Violators of these simple rules would be fined up to $2000 per violation. Who could be against that?

The corporations, of course!

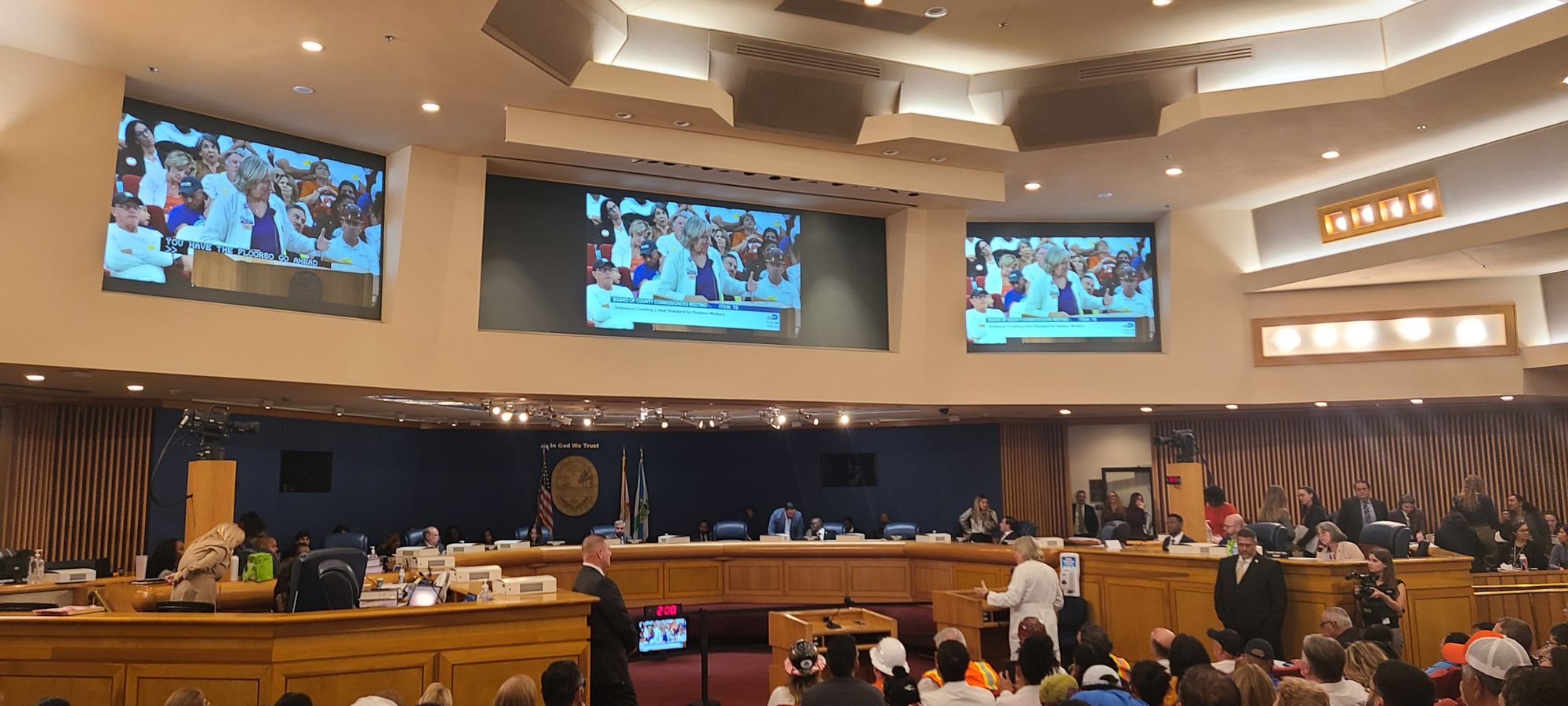

I attended the contentious county council meeting yesterday, where the council punted the ordinance until next year. Still, before I go into what I saw and heard, I want to provide some historical context to the situation in Florida.

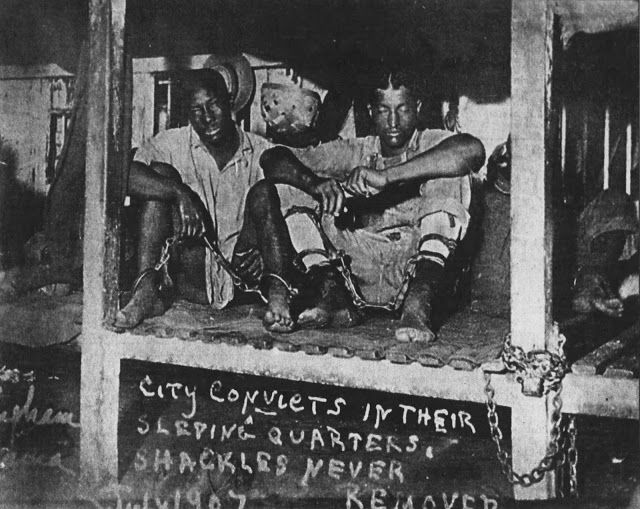

When the Civil War ended Radical Republicans understood that the war that had just cost the lives of 600,000 soldiers to end human enslavement in the United States required systematic changes at the national level to abolish slavery once and for all. The solution was the 13th Amendment of the US Constitution, ratified on December 6, 1865. The text of the amendment reads: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction (emphasis mine).” Note the part about the “except as a punishment for crime.” The former enslavers in the South exploited this clause and from 1866 until 1928 used a system called “convict leasing” to rent convicts to be used as forced labor. The former enslavers preferred this system over chattel slavery because it was cheaper. As one Southerner put it, if “one (convict) dies, get another.”[1] A classmate of mine at FIU studied this system of enslavement by a different name in her Master’s paper and concluded that Henry Flagler, one of the forefathers of Miami, whose statue sits in front of one of our courthouses, used this system to build many of the roads here in Miami-Dade County and at least one of his hotels.

As awful as the system was, the people using it were tired of it because it was deemed unnecessarily expensive, given they had to provide food and water for the convicts they had leased. As historian Mathew J. Mancini concludes in his outstanding study of convict leasing, aptly named One Dies, Get Another, the practice was eliminated because of “loss of revenue” combined with an increasing public awareness of the barbarity of the practice and subsequent efforts to abolish it.[2] In other words, it ended because the corporations and employers of the system were losing money, and they were getting bad press.

Fast forward to yesterday when Commissioner Danielle Cohen Higgins railed against an ordinance to provide shade and water to workers in excessive heat because it would be, in her estimate, too expensive and it would “potentially [the] kill industry” of agriculture in Miami-Dade County. That’s right, her top concern was “killing,” her word, not mine, industry, not that industry is killing workers. To defeat the measure, Coehn Higgins also said that OSHA covered the workers anyway (it does not), that the ordinance would create a new department in the county (it would not), and that it is too long, noting, I’m not making this up, the ordinance includes requirements for employers to post the ordinance where workers can read it. One of the sponsors of the ordinance, Commissioner Kionee McGhee, turned to the county lawyer to confirm that on the record, Cohen Higgin had lied or misrepresented the ordinance and its impact on multiple accounts.

All of this was after industry supporters, apparently tipped off to the fact that the commissioners would not allow public comments on the ordinance—a rare refusal to allow comments—showed up en masse to block the workers who would be protected by the ordinance from attending the meeting. The meeting doors opened at 8:45 for a meeting scheduled to start at 9:30. I was there by 8:00, got in line to attend the meeting, and was so far back that I was one of the last people to get in. Hundreds of outdoor workers were left in the lobby.

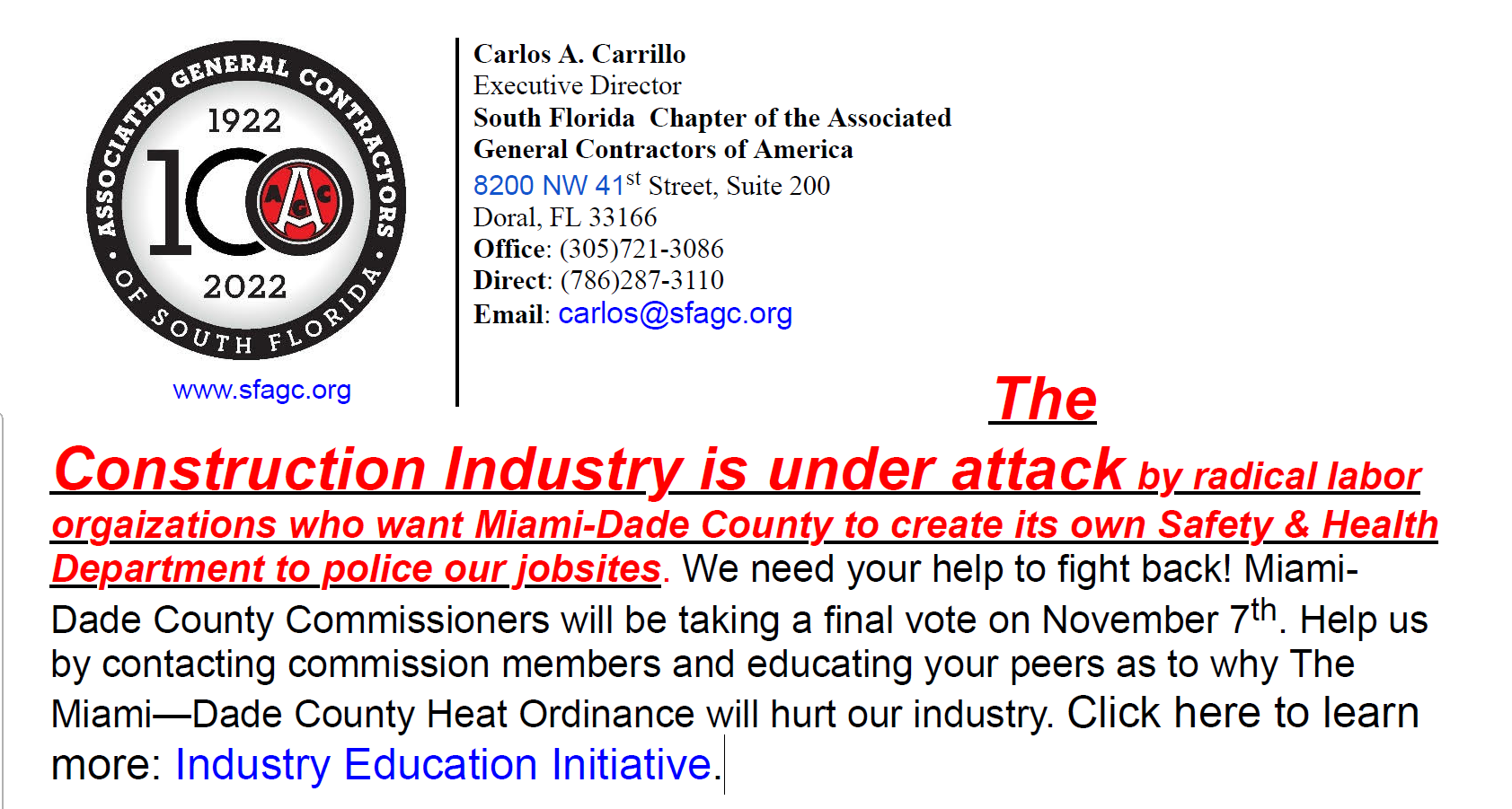

Someone told me on social media that they worked for the industry and were asked to attend the meeting to oppose the measure—they emailed their commissioner in support of the measure instead. The email from the industry leader screamed in large, bold, italicized red letters: “The construction industry is under attack by radical labor organizations who want Miami-Dade County to create its own Safety & Health Department to police our jobsites (sic).”

Trump supporter and vice chair of the commission, my commissioner, Anthony Rodriguez, took the opportunity to show the full commission the support represented in the chambers by asking the supporters of the workers and the ordinance to stand. Perhaps two dozen of us stood. Then he asked for opponents of the ordinance to stand—these are the people who got there apparently at least an hour before the meeting—and they did, maybe as many as two hundred of them. Yet, it was estimated that five hundred people were in the lobby waiting to get in to support the measure, commented on but unseen by the council.

Vice Chair Rodriguez was magnanimous enough to allow people in support of the ordinance one person to testify on behalf of the ordinance. The ordinance sponsors asked an ER doctor to take the podium, but as the meeting went very long, the doctor had to leave before he could testify. Instead, an ER nurse testified that not only had she seen workers die in her ER from heat exposure, but she also commonly saw the heat cause renal failure in workers in her ER. She noted that many workers wear diapers in the fields because they are not even allowed to take bathroom breaks.

The ordinance is not dead—like the people who let convict leasing die because it was unpopular, the people opposed to the ordinance cannot openly admit they don’t care if workers die. Instead, the ordinance will be brought to the County Council in March of next year. Hopefully, by then, public opinion will be so riled up by the barbarity of people dying in the fields, facing renal failure because of the staggering South Florida heat, and wearing diapers because they aren’t allowed bathroom breaks will be enough to pass this critical ordinance into law.

For information on the campaign for the Heat Ordinance, including how you can help, check out WeCount's Que Calor campaign page.

Mancini, Matthew J. One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

[1] Mancini, One Dies, Get Another, 3.

[2] Mancini, 216–17.