Black Civil War History in Florida

If you like history, especially American history, chances are you've seen the movie Glory, starring Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, and a young Andre Braugher, about one of America's first Black Regiments, the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The movie depicts the heroism of the unit during the Second Battle of Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, outside the powerful City of Charleston, South Carolina, and how, despite the ferocious fighting and skill of the 54th, the 54th was defeated, and Ft. Wagner never fell.

While technically true, this telling of the history is primarily told through the eyes of the protagonist of the movie, a young white man named Col. Robert Gould Shaw, who died on the Fort's walls that night. So, the film ends with Shaw being (illegally) buried in a mass grave with his soldiers, and the narrative that the fort never fell told on an epilogue screen before the end credits roll while one of James Horner's earliest and most iconic scores soars.[1]

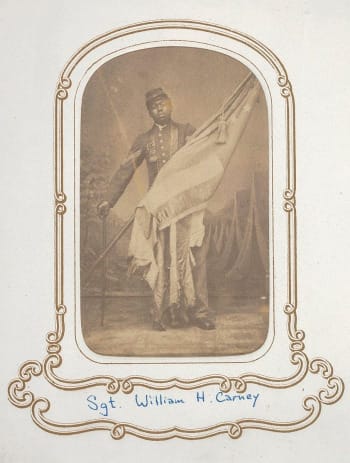

But this was only the beginning of the Massachusetts 54th's history. It ignores the fact that the Fort was abandoned a few weeks later and that the heroism of William Harvey Carney that night when he kept the American flag from touching the ground, even in retreat, became one of the best-known, most iconic retellings in the entire war. According to historian Douglas R. Egerton, “By the start of the twentieth century, the phrase ‘the old flag never touched the ground’ became one of the most popular across the North, and Carney’s words, one New Englander remarked, were 'known by every schoolboy in the land.'” William McKinley awarded Carney the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1900, none of which is accurately depicted in the movie.[2]

Thanks to the 54th's successes in the earlier battle depicted in the movie, the battalion's incredible race through miles of swamp overnight to get to Ft. Wagner, and their heroism in that battle, the 54th helped recruitment of Black men as soldiers surge.[3] While Massachusetts proudly gave her name to the 54th as well as the 54th's sister regiment, the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, other states in the Union refused to follow suit, forcing the US Military to designate the other Black regiments as United States Colored Infantry.

Undaunted, Massachusetts took this a step further, mustering and training the first Black Cavalry Regiment, the Massachusetts 5th Cavalry Regiment, which would later proudly ride into Richmond, Virginia, Capital of the Slaveholder's Rebellion, as "the first mounted men in the city."[4] This feat followed the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry marching into Charleston, arguably the most important city in the South, two months earlier, apparently singing “John Brown’s Body” alongside the 21st US Colored Infantry Regiment.[5] The 54th, which Glory suggests never conquered Charleston and indeed was annihilated years before the city fell, was one of the units tasked with imposing “order and a measure of justice on Charleston.”[6]

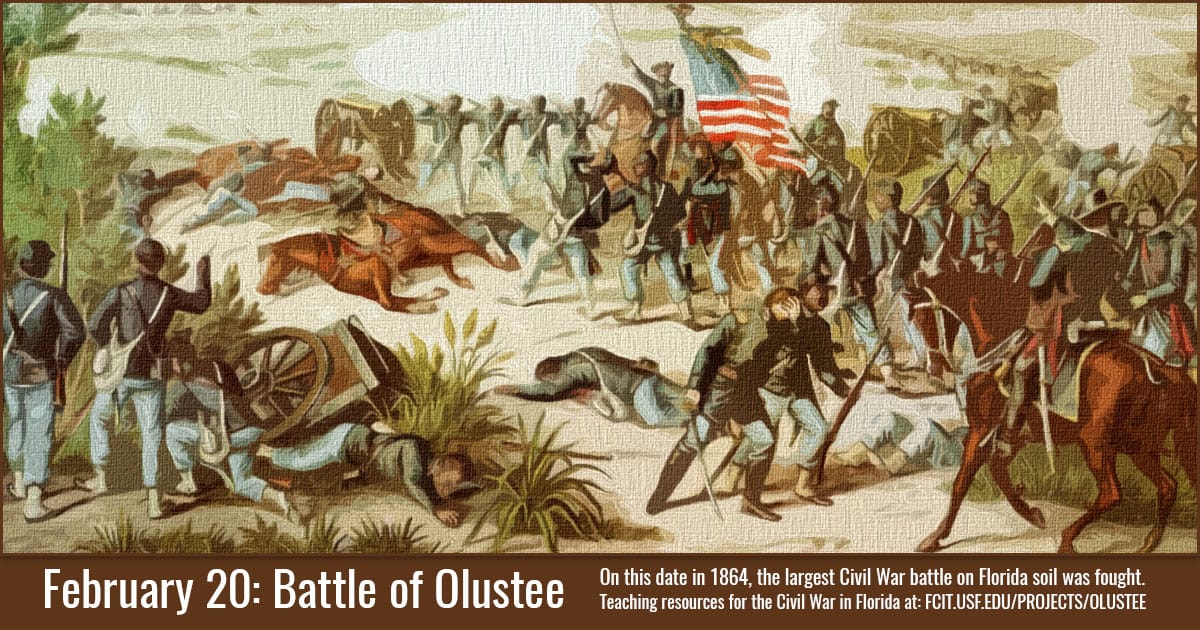

What does all of this have to do with Florida? Between proving their mettle in South Carolina and establishing peace in occupied Charleston two years later, the 54th was sent to Florida in the Winter of early 1864 to help the Union Army push west out of recently captured Jacksonville, Florida, to free enslaved people and to cut off Confederate supply lines. At the head of the march into Northern Florida were the 7th New Hampshire Infantry, the 1st North Carolina Infantry, and the 8th U.S. Colored Infantry. On February 20, 1864, the march was halted by a Confederate ambush of 5,000 soldiers near Ocean Pond, near Olustee in Baker County. With the 54th several miles in the rear, Union troops began retreating after suffering heavy casualties. The 54th was told to advance and cover the retreat of their fellow Union soldiers, Black and white, and, according to one, “saved the army.” The 54th fired their weapons until they ran out of ammunition and continued to stand their ground until all Union troops could retreat, even when left only with melee weapons and after their white commanding officer had ordered their retreat.[7]

This was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War, fought in Florida. There, not only did Black and white men fight, bleed, and die alongside one another for freedom and the United States, but the legend of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry continued to grow thanks to their bravery, resourcefulness, and refusal to retreat. These men and their families who struggled along with them, sometimes from home, sometimes from the battlefield camps themselves, fought for recognition (and pensions) as men entitled to rights equal to the white men they fought alongside and against.[8]

“Charleston in the American Civil War.” In Wikipedia, January 13, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charleston_in_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=1195367769.

Egerton, Douglas R. Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

Gallman, J. Matthew. “In Your Hands That Musket Means Liberty: African American Soldiers and the Battle of Olustee.” In Wars within a War, edited by Joan Waugh and Gary W. Gallagher, 87–108. University of North Carolina Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.5149/9780807898444_waugh.8.

Orlando Sentinel. “THE 54TH REGIMENT FOUGHT IN FLORIDA,” April 14, 1991. https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-xpm-1991-04-14-9104131225-story.html.

Pinheiro Jr., Holly A. The Families’ Civil War: Black Soldiers and the Fight for Racial Justice. Uncivil Wars. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2022.

Polowy, Kevin. “Perfect Scores: James Horner’s Most Memorable Movie Music.” Yahoo Entertainment, June 23, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20171129094540/https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/s/james-horner-best-music-scores-soundtracks-songs-122229769312.html.

[1] Polowy, “Perfect Scores: James Horner’s Most Memorable Movie Music.”

[2] Egerton, Thunder at the Gates, 315.

[3] Gallman, “In Your Hands That Musket Means Liberty,” 90.

[4] Egerton, Thunder at the Gates, 274–76.

[5] “Charleston in the American Civil War.”

[6] Egerton, Thunder at the Gates, 294.

[7] Gallman, “In Your Hands That Musket Means Liberty,” 88–91; Egerton, Thunder at the Gates, 219–25; “THE 54TH REGIMENT FOUGHT IN FLORIDA.”

[8] Pinheiro Jr., The Families’ Civil War.