Thoughts on books and bookstores

Why I provide the book seller links I provide and how I evaluate the merits of a non-fiction book

I wanted to offer some thoughts on how academics evaluate the merit of books and why, when I provide a link to a book, it is usually (always?) to either biblio.com or indiebound.org

Why biblio.com and indiebound.org?

My sister-in-law has, for most of the time I’ve known her, and I’ve known her for over twenty years, worked at an independent (indy) bookstore called Malaprops in Asheville, North Carolina. If you’re a bookstore nerd in the Southeast you’ve almost certainly heard of it, if not been there. If you are a bookseller in the United States, you know the store. A few years ago my sister-in-law purchased the store. She hammered away for years at me at the importance of local booksellers and, if you can’t do that, at least brick and mortar stores, such as Books-a-Million or Barnes and Nobel. Buying from local booksellers supports the local economy and supports a diversity of books. Though I buy from Malaprops often, I know other people have either a preferred local indy bookstore, or want to have one. So, I point people to indiebound.org, a website committed to getting readers to local booksellers, even if only online.

Biblio.com was started by one of my sister-in-law’s coworkers to help people find used books from used booksellers. It’s great to buy books new so the author get the most from the sale, but every author knows, that’s not always possible. So they are happy when you buy the book used. And every author I know prefers you buy them from indy booksellers.

How do academics evaluate if a book is worth reading?

As you dive deeper into a nonfiction subject you’ll eventually find that not all books are equal and some are just plain bad, misleading even. So how do academics, experts in learning new knowledge (hopefully) go about discovering new books to read? Princeton University has some thoughts that you can find here. They are much more concise than what follows, but they are also meant to guide students looking to write research papers.

For me, from what I’ve been told by professors in a range of topics is to look at what follows. These are general guidelines I use. I will note that none of these are deal breakers—it can be lacking in one or more of these and still be good, with one exception. Notes. If the book doesn’t bother to provide sources it isn’t to be taken seriously. It might still be fun though!

Who wrote it?

- Is the person an academic associated with an institution? This matters because if they publish crap it could get them in trouble with their employer, and if they do not have tenure it can lead to quick termination. So people associated with universities are very careful in what they publish!

- Are they writing in a field in which they are trained? A few years back a book called Caste came out to much fanfare. It was called a history book though it was written by an journalism professor, not a historian. It won many awards. And it was shredded by many historians as being simply not accurate history. The book is well written, perhaps worth your time, but it’s not going to be assigned in many history classes because, well, it’s not up to academic standards for the field. The author is an outstanding journalist, but when it comes to academic studies in a different, though related field, the author struggled, in no small part because the author chose to publish for a trade press instead of a university press.

Who published it?

- Is it a university press or a trade press? University press (UP) published books tend to be more expensive, less accessible and, crucially, peer reviewed. You probably own some books by Oxford University Press or Princeton University Press, which are great presses. But the University of Florida Press, though less well known, is just as good at providing sound information. Why? Because they are peer reviewed, which means experts in the field have been given the manuscript and been told to make sure the author isn’t making mistakes. Trade press books, such as Penguine or Random House, though big publishers who can get the word out about a book, generally do not use peer reviews. Take the example above of Caste. Caste was published by Random House. Random House is a reputable press; they do not enslist experts in the field of their books to check for mistakes. Had the author of Caste tried to publish in a university press they would have produced a more accurate book. However, because of the academic rigor behind it it would have likely taken longer to publish, if it ever met the standards to be published at a UP, and it would not have received the publicity that it did (Random House got Oprah to call it one of her books of the month). Is it possible for a worthwile book to come from outside a university press? Of course it is. It is just harder to do and if I’m evaluating a book that is not published by a UP I’m going to look harder at the other bullet points listed here.

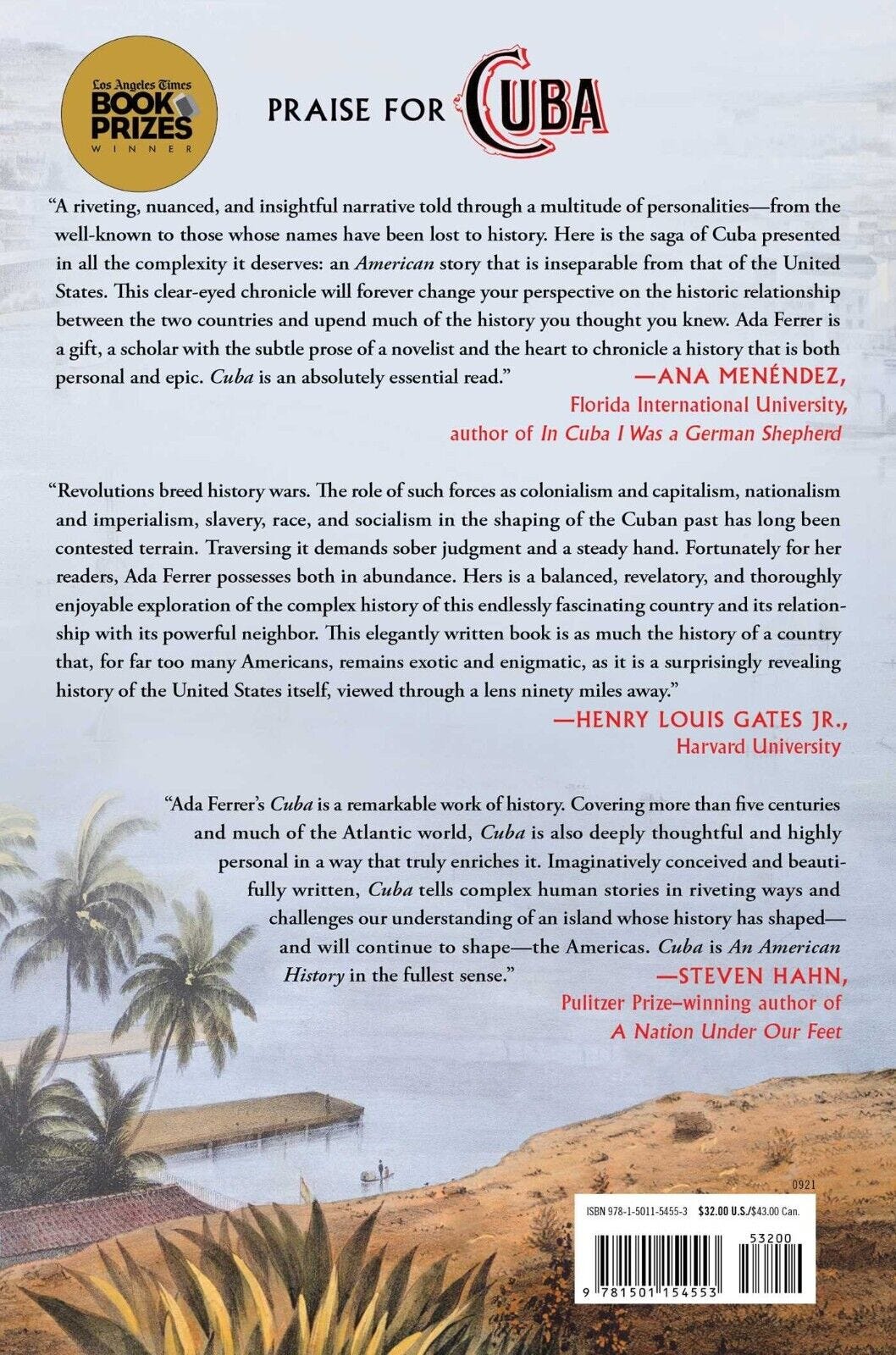

Who blurbed it?

- Who wrote a little review that’s on the back cover or inside pages (these are called blurbs)? Oprah writing a blurb on a book is great for selling the book (and if I ever publish a book I would cut off a toe to have Oprah write a blurb for my book) but it does not mean that the book is necessarily sound research/facts. Though for a popular book you’ll often find them in the inside pages of the book, I look to see, which professors from what university wrote a blurb. Are there none on the book? Hmm, that’s suspect. Did one of my most trusted sources, historian Heather Cox Richardson write a blurb? I’m picking that up. The vast majority of books are in the middle of course, but having a historian at the University of Chicago take the time to write a blurb on a book means more in terms of if it is a good history/sociology/physchology, etc book than say, Jimmy Fallon writing a blurb on it.

What are the notes like?

A book that has no notes in the back (or at the bottom of pages in some cases) and no sources is not even attempting to provide academic quality work. They are publishing quickly either to get their thinking out in public, or more likely, to make a few dollars. Well written and argued academic books might, in extreme cases, have up to half the pages be dedicated to notes, sources, appendicies with methodology and an index. More common is perhaps 20% of the pages containing the notes etc for the book. If it is only a few pages, perhaps a “select bibliogarphy,” it is not something an academic is likely to take seriously.

When was it published?

- Though we like to think of things as having universal truths, the simple reality is, our best understanding of any given subject will change over time. There are many reasons for this, even in the humanities. An extreme example of this is Black Reconstruction in America, first published by W. E. B DuBois in 1935. Though the book is considered by most historians to be a masterpiece of historical research, rich in still relevant information, the simple fact of the matter is, DuBois didn’t have access to all of the resources even a white contemporary would have had in the 1930s—because he wasn’t allowed in most libraries or archives, where important knowldege is stored. One might argue this is the greatest history book about American history ever written, one of the most impressive books in the English language, and yet its age is a significant factor in maintaining accuracy due to the conditions the author was forced to work in but also the technological limitations of the time he wrote it. That’s an exteme example, but most other academic fields have changed over time because of simple and more begnign things, such as digitalization and transportation improvements. I simply have more access to historical information and documents right now from my computer than any one who had ever lived in 1980. Which is not to say that everything of value is available online. Far from it! Most things are not, believe it or not. My master’s paper was largely based on a 100 page document distributed to police unions in 1974—it’s possible, if not likely, that I was looking at the only copy still in existence. And that’s a document from 1974, when photocopying was a widely used technology, making mass production easier. Also, there’s more research! A book written in the last ten years is hopefully pulling from research from the previous studies, which for a topic such as American Reconstruction, date back to late 19th century. Still, Black Reconstruction should also illustrate the point that recency isn’t everything. An old book can be quite useful, especially if the subject hasn’t been visited in a while by researchers, which happens more often than you might think!